“Oh, Gorels!” when the then 5-year-old boy Chance was brought by his parents to befriend a kid of his opposite sex, he simply uttered so, though vaguely, to the girl in front of him. It is surprising to think how our society is able to so efficiently implant the fixed ideas differencing girl and boy, male and female already from such a young age. Spinoza explained “ to define what something is always starts from what something is not.” Already in 1959, the American psychologist Ruth Hartley pointed out that the little boy learns how not to behave before he learns how to behave in order to be masculine. For the boy, everything that is not feminine is masculine. So then, what is the girl and what is feminine?

“ Qui est la jeune fille?” ( What is the girl?) For Simone de Beauvoir, The Girl was a crucial figure in the project that would become The Other Sex. She described The Girl as in the stage between child and woman, in the transition between childhood and adulthood. The Girl is both being a girl and becoming a woman. “Becoming a woman” is de Beauvoir’s strong contribution to the foundation of feminism thoughts in which the female body is seen as a significant site of the process of becoming. De Beauvoir drew our attention to the body of The Girl as the physical transformation at this stage that paves the way for the becoming of womanhood. The body of The Girl is the source of her emotional turmoil. She feels uncertain, both proud of her body and feels awkward in it. She turns into a narcissist, a dreamer who seems to endowed with magic virtues yet she is growing anxious towards her own femininity. At the awkward age of The Girl, she tests the world with eyes and head, but also with mouth and stomach. When she feels not being loved, The Girl goes to the nature and she feels, records and observes the world passing by as she transcends and becomes the woman-to-be.

Simone de Beauvoirr’s existential insights over The Girl provide us a feminism reading of the artworks presented in this exhibition. In Wang Jiaxue’s Tired Romantic we see a young individual caught in a half-wild and half-tamed body. She stares at the world as the world reveals in her over-sized eyes and in them we can read longing, fear, hope and despair. In Wu Di’s Twin Sisters, two girls turn against us facing whatever in front of them in the dark. Tragic or hopeful? We are left in bewilderment. In Qin Qi’s Wind, a girl in restaurant worker’s uniform sinks into daydream as she takes a short pause from her daily work. Is she dreaming of her love like Cinderella dreams of her Prince Charming? For the young girl, erotic transcendence includes in the process of becoming woman. In Shen Ling’s painting we meet two seemingly quite bored young girls sitting at a richly decorated banquet table unable to be happy. Passivity is The Girl’s instrument for grasping power. A girl’s narcissism and bodily self-destroying lie not just on looking at the mirror with a blind eye (as in He Sen’s Make Up 1), she tests the world with her own body parts. The cut on the girl’s thigh in He An’s photograph screams for pain and yearns for affection. Schopenhauer sees boredom and pain as two evils of life, yet, it may as well be the calls for attention and the sources of creation.

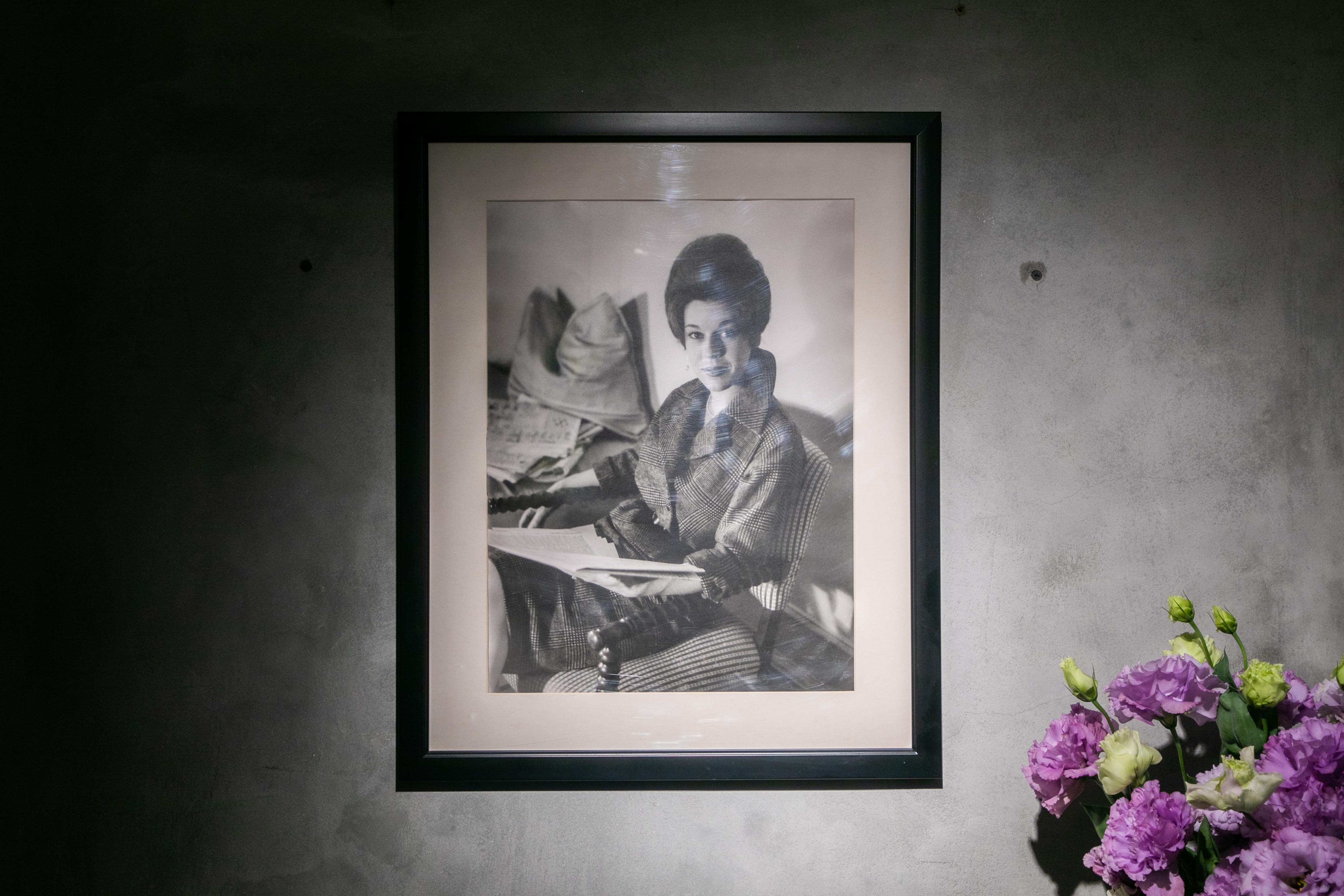

Certainly we can not talk about femininity without the gaze from the other sex. When Yu Youhan merged two of the 20th century’s most iconic images, Mao and Monroe, into one, he has also merged two symbols that both strive for control: power and sex. While Liu Jianhua’s porcelain female body is provocative in objectifying womanhood, the fine quality China tableware also grow uncomfortable association when the work echoes an old Chinese saying: women as candy for eyes and for mouth, Yuan Yuan disguises both the intention and the motive in his painting behind the camouflage color and pattern. In Japan, pornographic films are also screened under the disguise of mosaic on women’s sex,a social moral smokescreen for justifying the industry of female body trade. I have always wanted to find a feminism reading in Yang Fudong’s body of work. There is always a strong female figure standing in the center of his creation, may it be the daughter-in-law of the family who determined to move the mountain (Moving Mountains) or the self-possessed Ms. Huang at M. Last Night” (2006) fascinated, not necessarily merely male viewers. Yang Fudong’s female image has the power to step out from the shadows of men and establish her own authority. Such power in Yu Hong’s works on glasses are transformed into eulogy for girls in nature. Beauty breathes there. Light shines there. The fragility of the glasses lands softly on the vulnerability of the girls. For Yu Hong, it has to be autobiographical. The art history’s most enigmatic gaze is disguised behind Liang Manxue’s Little Princess. Running through the historical corridor, the girl’s becoming of woman has to overcome layers of man’s gaze.

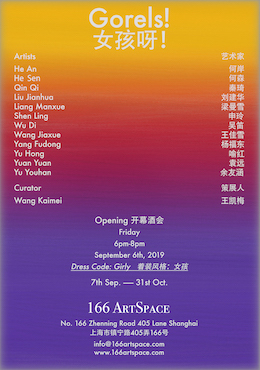

This exhibition has gathered paintings, photographs and sculpture of 12 Chinese artists from Lingling and Andrew’s collection. They all have female protagonist(s) covering the stage from the transitional girl to the woman-to-be. Each individual work addresses, to certain extent, our discussion on femininity, some reconfirm the stereotypes; others confront the social norms, one of which being the makers of these images just as the makers of the social norms implanted to femininity are still predominately men. These are enough urgent reasons for a show addressing the myth of Femininity to be opened here. Hopefully the exhibition could trigger more discussions around femininity issues both in the art world and in our society in general. Please be reminded by Simone de Beauvoir, the woman who laid the foundation for our modern times gender study: One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.

几年前,Andrew和龄龄才5岁的儿子被爸妈带到朋友家中做客,成年人习惯性地把家中同龄的小孩叫出来,让两个孩子成为朋友。“女孩呀!” 男孩子用男子汉的口气对面前的异性小朋友嘟囔着。这样的场面许多家长也一定目睹过,对于性别的固有认知就是如此有效地将男孩和女孩,男性和女性的区别早早地灌输到一个人的成长中。斯宾诺莎说:对于是什么的定义,首先是从它不是什么开始的。早在1959年,美国心理学家Ruth Hartley就提出,男孩在学习怎么成为男人的时候,首先学到的是不应该做什么,凡是不是女孩的,那就是男孩的,那么,女孩又是什么呢?

“ Qui est la jeune fille?” ( 女孩是什么?)“ 在西蒙·德·波娃的《第二性》中,女孩是一个非常关键的人物。她通过对于女孩的描述,启蒙我们对女性特质起源的认知。女孩是一个未来的女人,一个在童年与成年过渡阶段中生长的个体,她处在一个从孩子成为一个女人的中间地带。“女人是成为的”,这是德·波娃创立的女性主义理论的基础,而成为女人是从女孩对自身身体的感知开始的。在成为女人的过程中,女孩开始发育的身体成为她情感剧烈变化的宣泄地,一方面她为自己身体拥有的魔力沾沾自喜,另一方面,她又在为身体显露的女性特质开始感到惴惴不安;她的身体附着在女孩时的独立和即将成为女人的服从之间,喜悦、不安、骄傲、梦幻...她自恋着,梦幻着,用眼睛、头脑体验世界,也用唇齿、肌肤感受世界。她要去爱,也要被爱,在大自然中,感受、记录、观察,看着世界在她眼前展开,直到超越自己,成为女人。

西蒙·得·波娃对于“女孩”的存在主义思考,为本次展览的作品提供了来自女性主义认知的解读。在王佳雪的《疲倦的浪漫》中,一名身体处在“一半是狂野,一半是驯服”状态中的女孩与我们对视,世界在她睁大的双眼中显象:希望、失望、恐惧、向往;在吴笛的《双生姐妹》中,两个女孩背朝我们,面对她们的世界隐于暗处,悲情还是温情?我们禁不住担忧。秦琦的画中,《风》从一个陷入白日梦的年轻的餐馆女服务员身边飘过,和迪士尼的公主梦一样,她也在梦她的白马王子吗?在女孩身体的自我觉醒中中,性觉醒是成为女人的重要一步;申玲的画《伤感》,那两个显然不开心的女孩,面对一桌子的美酒佳肴,却无法快乐起来。女孩会把柔弱和被动作为获取权力的方式,并在自恋和自残的交替进行中,获得个体独立。何森的画上闭着眼睛化妆的女孩,何岸的照片上布满伤痕的“小不点”,都是女孩成长中必经的,生活的无聊乏味和寻求刺激的肉体伤害。就如叔本华的认知:无聊和痛苦是人生的两大邪恶,然而,又何尝不是呼唤关注和萌发创造力的源泉呢?

当然,在这个讨论女性的展览上少不了来自他者的注视。当余友涵将20世纪两个最著名的人物:毛泽东和梦露,混淆在同一张画面的时候,他也在将两个追求控制的符号合二为一:权力与性;刘建华以陶瓷为载体塑造的“中国女子”无疑在挑战物化女性的话题,高质量的中国瓷器与烧造餐盘的原料同处一炉,在男权专制的传统社会里,女性身体”秀色可餐“的比喻令人感到不适。袁远将作品的内容和主题都隐藏在迷彩图案中,在日本,成人电影的女性性器官上也会被打上马赛克,是社会法令的制定者们在道德与女性身体贸易间挂起的遮羞布。杨福东的作品是物化女性呢?还是歌颂女性?我一直想从女性主义的角度去解读他的角色。杨福东作品中的主角常常是一些性格强大的女性,《愚公移山》中,他的关注点不是那些挖山的男人们,反倒是能够让这个挖山的行为“子子孙孙”传递下去的家中的媳妇;《国际饭店》系列中的女性,那些自我陶醉的女人们吸引的并非只是男性的目光,她们具有从男人的阴影中走出来的力量,展现独立和美丽的自我个体。这种力量也从喻红画在玻璃上的在大自然中的裸体女性的作品中传递出来,美人佳境,玻璃材料的美丽易碎反射出女孩成长的脆弱敏感,对于喻红,这必须是源自女性身份的自我反思。绘画史上最大谜团的”小公主”的注视,被梁曼雪覆盖上更神秘的面具,女孩是在充满男性目光的历史长廊里一路狂奔成长为女人的。

这里展出的12位中国当代艺术家的作品都来自Andrew和龄龄的个人收藏,无论是绘画、雕塑和摄影作品,这里的主人公都是女性。她们跨越从女孩到女人的转变进程,从不同的角度回应关于女性成长的各种讨论,有的是对固定成见的确定,有的站在社会成见的对立面,这里包括我们立刻面对的,这些艺术作品中女性形象的创造者,就如在社会中对树立女性偏见的立法者与舆论建立者一样,大多数时候都是男性。这些足以成为这个展览存在的理由,并且由此展开围绕女孩成长和女性特质,在艺术领域和当代社会的思考讨论。这里,为当代女性问题的讨论奠定了基础的西蒙·得·波娃的言论依然有效:女性不是生而具有的,女性是后天成为的。