Painting has long courted existential risk. Philosophers, theologians, conceptualists and technophiles among others have and continue to mount well received campaigns in search of an elusive coup de grace. The medium’s survival is alternatively seen as obstinate persistence or miraculous redefinition.

Painters such as Han Jia Quan decline to be corralled into a choice between death and resurrection. Rather they balance painting’s capacity to convey meaning across generations with the heavy weight of their audience’s limited time. To do this effectively work needs to embrace the crush of present triumph and trauma without assuming any specific familiarity on the part of the viewer. Patience is required.

Han is at peace with the pedantic pace of art’s narrative. He may find the tempo frustrating, but he has the courage to continue to advance a series of compelling explorations without urgent regard to progress or resolution.

Some examples:

Color: Much of Han’s palette is aggressively muted - black and white, greys and dull browns. The introduction of color comes as a dramatic intervention rarely in the form of primary actors - burnt orange, rust, turquoise, a continuum of green and blue, dark yellows and pinks edging on vermillion. Color for Han seems less rebellion vis Matisse or a reduction cum Mondrian rather a poignant recognition of bit player’s profound contribution.

Structure: The artist‘s canvases of late focus on a shift from still life to forms of figuration. The former eschews the calm precision often associated with the oeuvre opting instead for spiky violence and appealing if chaotic coloration. Figurative works tend towards disembodiment - headless torsos as background for haberdashery and accoutrement - unattached hands engaged in a variety of compelling mischief. When full visages and figures are offered, they seem either ambiguously exaggerated (absent either sex or satire) or strangely divorced from content.

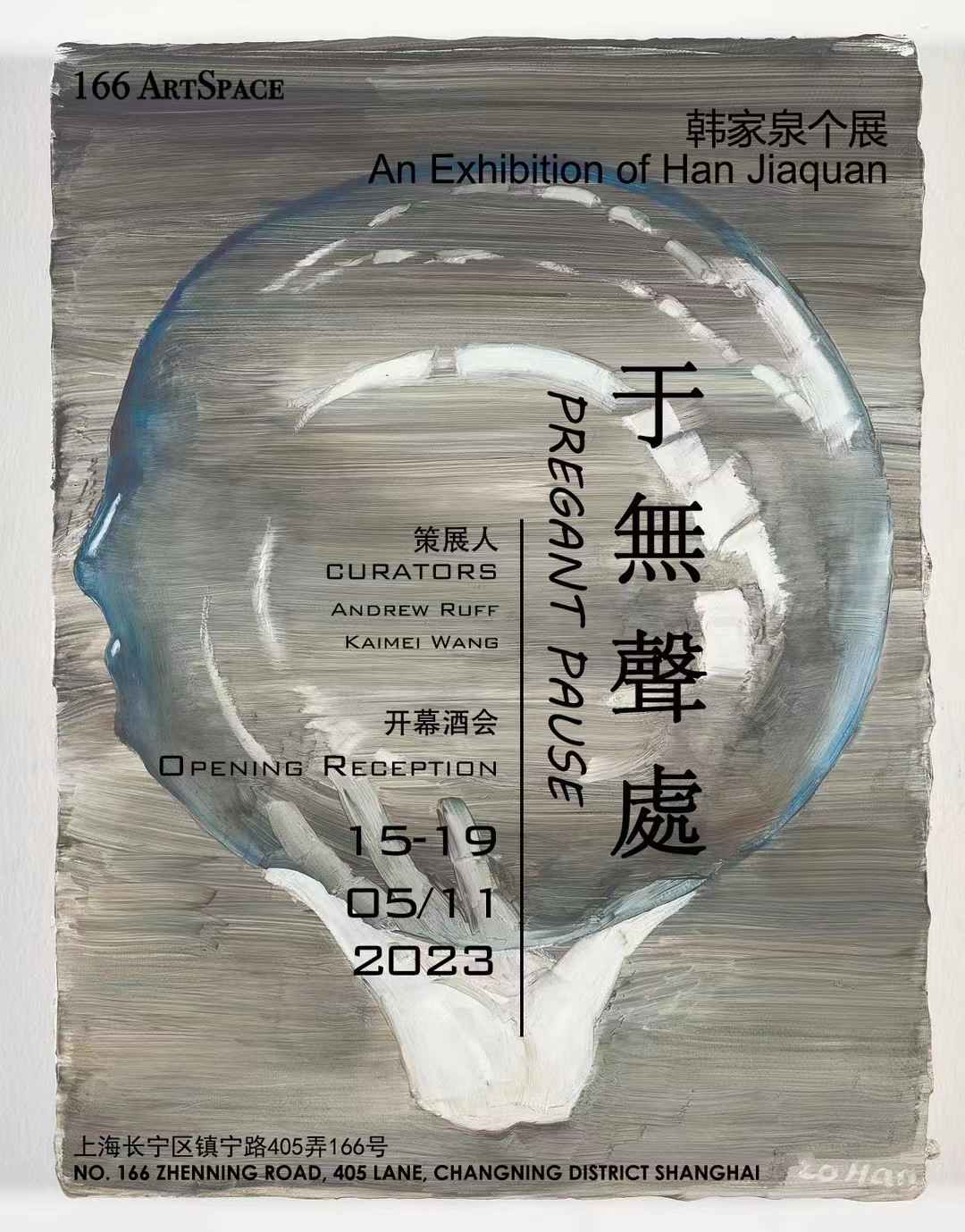

Mechanics: Han’s use of technology in the presentation of painting is delightfully antiquated. In the current exhibition he mounts six diptychs alternatively on motorized and hand cranked stands. Engaged at sufficient speed, the stands cause the paintings to blur into a single work - placing a figure into an empty scene or adding color to a muted subject. Less mechanically innovative than the most modest of displays in a 19th century World Fair, these works are surprisingly both addictive and contemporary.

Quixotically consistent, Han’s paintings are difficult to interpret as messages. A melange of references from renaissance to punk are poignantly chosen but oddly orphaned from context. I do think the artist’s investigations contrast curiously to some of the euphoric critical responses to recent exhibitions. Roberta Smith of the New York Times swoons in her review of the African American painter Henry Taylor’s survey at the Whitney that he as “reinvented the medium” without apparent need to reference alteration much less reinvention of the medium of painting at the hands of the artist. Perhaps more “medium” relevant experiments such as MOMA’s launch of a multi-screen display of AI algorithm generated non repeating amalgamations of works in its permanent collection are a better measure of art’s enduring relevance. Enthusiastic as they are about the foray, responsible MOMA staff appear more encouraged by its capacity to promote rather than to produce art.

Han Jia Quan’s sublime work purports neither to deliver transcendent comfort nor to wallow in present umbrage. It offers no obvious interpretation in terms either of pathos or polemic. His portrait of a prepubescent Spanish princess spinning into color on a hand cranked stand burns seductive neural pathways without seeming to pander to or divert our shock at the ongoing slaughter of sanctuary and prospect. Why is this? Let’s wait and see.

绘画这个最具世俗影响力的艺术媒介,一个具有古老传统的社会文明的载体,人类精神的归宿,同时,在它漫长的历史中,又是一个不断被挑战,被革命,被推翻,被重建的生命力强大的事物。在艺术史上,绘画被多次宣告死亡,但又总是能够成功地在那些预示自己死亡的机制中,不仅起死复生且倒戈制胜,持续保持新鲜感,用各种面相挑战创造者和观众。韩家泉和众多艺术家同行们,就是这些从“绘画已死”的危言耸听和“媒介重塑”的当下话题中,以绘画为行动走出自己路径的突围者之一。

这里略举几例:从色彩上看,韩家泉的绘画中大部分色彩都非常柔和——浅黑、灰白,棕黑、暗紫…色彩在韩的画中如隐于幕后的戏剧性干预,虽不像马蒂斯的叛逆,也不同于蒙德里安的简约,而是将画中物与物的关系用色彩联系起来的探索。从画面的布局结构上看,完美静物到缺失部件的玩偶身体,没有面孔的人物画像,一种怪诞惊悚的暴力美学,却总不失时机地报之以柔和色晕,带来具有体感的温情。机械性:古老的“残影余像”技术为展览中用手工或马达运动起来的双联画,令人想到19世纪世博会上惊艳巴黎人的奇观,在此刻被添加上一种出其不意的当代性,朴素技术对高科技AI巧妙的一计反手勾拳。

韩家泉对绘画的坚持,可以用来回应最近一些权威专家对绘画的批判。例如,近期《纽约时报》的著名艺评人罗伯塔·史密斯(Roberta Smith)在评论非裔美国画家亨利·泰勒(Henry Taylor)在惠特尼美术馆的回顾展时表示,艺术家“重塑了媒介”。也许更加重塑媒介的是MOMA推出的人工智能算法不断输出画面的屏幕,当这些耀眼的电子产品与博物馆的经典收藏并排出场的时候,何为艺术的经久性?到底孰是孰非?MOMA的馆员们对AI的突袭充满热情,但让他们兴奋的似乎更是这片屏幕推广艺术的强大力量,而不是AI生成的艺术本事。

对于像韩家泉这样诚恳的艺术家,他们的绘画带领我们走进人性深层的记忆、情感、痛苦与快乐的栖居地。如果说关于绘画的讨论是一场艺术舞台上史诗级的连续剧的话,韩家泉在台上的“策略型停顿”(本次展览英文题目“Pregnant Pause”的直译),西班牙小公主在手摇支架上淡入淡出的情景,打开令人兴奋的神经通路。为什么会这样?于无声处,拭目以待。